Taking notes & good science

You can’t have good science without taking notes unless you remember what you had for lunch 58 days ago. Science is about forming consensus and being able to replicate experiments. How can you repeat what you don’t remember? Have I convinced you? No? Then leave. Don’t read the rest. Have you convinced yourself now? I hope so… grrrrrrrrr

Googling brings up some good things about note-taking in general:

Cornell Method: Divide your notepaper into a main notetaking area, a cue column, and a summary section. It is a valuable technique for organizing information and reviewing notes later.

Mapping: This visual way of note-taking involves creating a diagram or mind map of related concepts and ideas. It is helpful for brainstorming, problem-solving, and understanding complex relationships.

Charting: Charting involves creating tables, graphs, or charts to organize and summarize information. It helps compare and contrast concepts, data analysis, and identify patterns.

Outlining: Outlining involves creating an organized information hierarchy using headings and subheadings. It helps summarize and synthesize information and identify the main points of a text.

Sketchnoting: Sketchnoting involves combining images, icons, and text to capture information. It is helpful for creative thinking, engagement, and making connections between ideas.

Getting Things Done (GTD) is a productivity method that involves capturing all your tasks, organizing them, and prioritizing what’s important. It helps reduce stress and increase productivity by keeping a clear mind.

Zettelkasten: This notetaking system involves creating small notes containing individual ideas or concepts and linking them together using a unique identifier, allowing for complex ideas to be built and connected over time.

The last two items are systems for notetaking. If something has at least two approaches, we can call it hard; you must agree, no?

As a beginner, how do I approach notetaking?

Start writing on a scratchpad. A scratchpad is like a piece of paper where you can write things down. Registering on it lets you organize your ideas, make plans, choose what is most important, and remember things you want to remember. For example, write down things you hear in a class or a meeting, when you want to think up new ideas, or when you have a problem to solve. You can also use it to draw pictures or write whichever way you like, and you don’t have to be perfect. This process helps you to be more creative and make more things, and later you can use what you wrote as a reminder of what you learned or want to do. The first five methods of the list above can be mixed for this goal. There’s no wrong way. The cue phrase is “brain dump”.

This is me:

I have hundreds of pieces of paper everywhere from scratchpad. What do I do with them?

This is the moment notetaking systems take over. I recommend reading “How to Take Smart Notes” from Sönke Ahrens. I don’t know how to motivate you to read that book. I will say that Niklas Luhmann, who pioneered this method, authored over 70 books and close to 400 scholarly articles on diverse topics such as law, economy, politics, art, religion, ecology, mass media, and love. How can I person write 70 books in one life? When asked this question, Niklas would point to the old file full of card notes. Thank god we have digital notetaking.

Which software should I use to manage my notes?

Well well well… The list is long:

- Roam Research

- Obsidian

- Zettlr

- The Archive

- Foam

- Notejoy

- TiddlyWiki

- nvALT

- Simplenote

- Evernote

- Standard Notes

- Keep It

- DEVONthink

- ConnectedText

- Luhmann’s Zettelkasten

- Notion

- Citationsy

- Zettel

- Joplin

- Trilium Notes

I hope I have answered your question… Good luck with the information overload :)

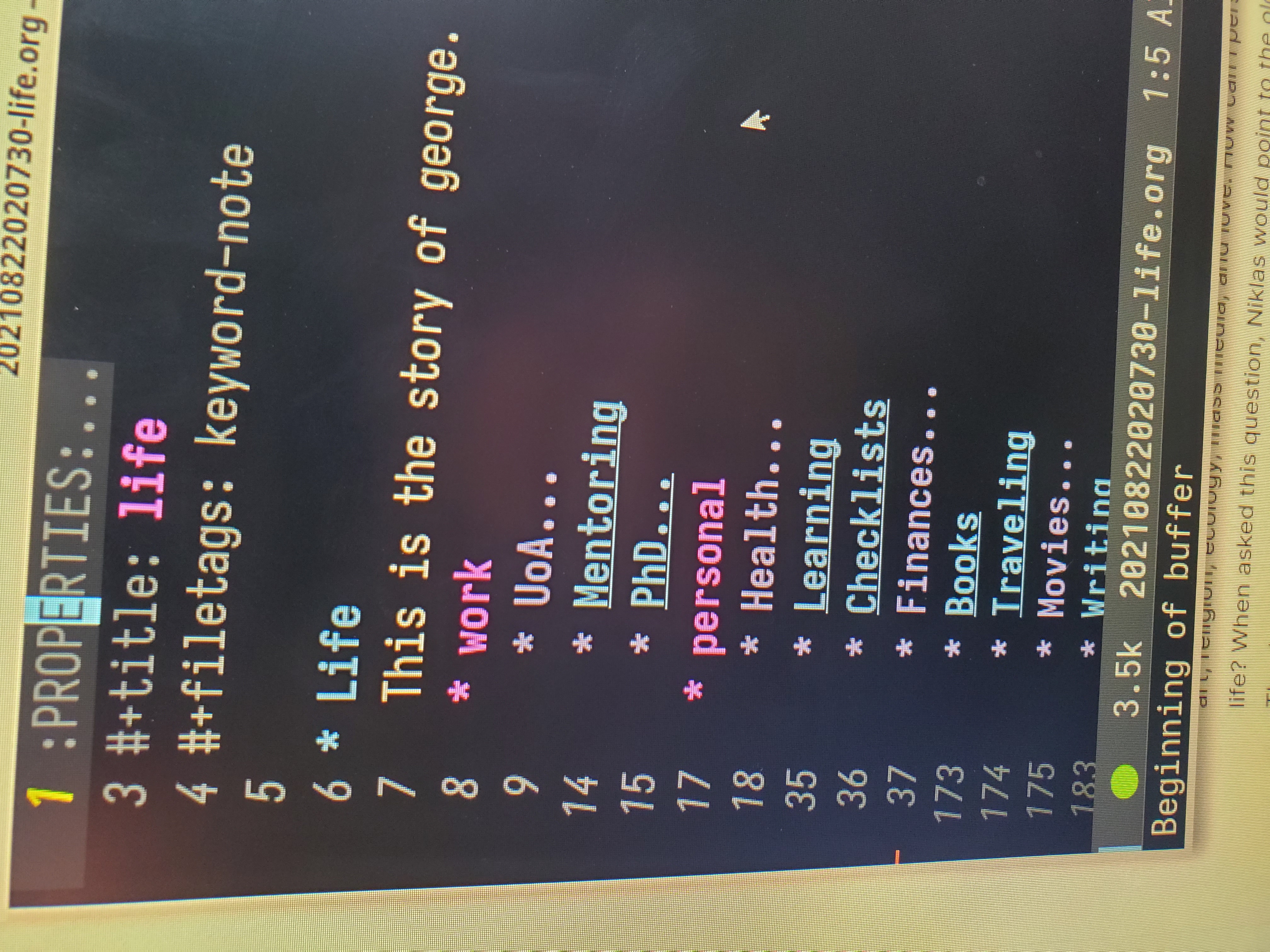

If you want my opinion, go with Obsidian. It is free for personal use. I use emacs and org-mode, but I am utterly insane beyond insanity. So you don’t want to come down here.

This is emacs:

How can this help my science in practical terms?

Simply put, this will help you by preventing overload.

Information Overload: Scientists are constantly flooded with new data, research papers, and scientific studies that are sometimes difficult to process, analyze and identify legitimate findings. Information overload can lead to a misinterpretation of data, incorrect conclusions, and wasted resources.

Choice Overload: Sometimes, scientists have to choose between different options or methods to conduct their research. Too many choices can lead to indecision, wasted time, and missed opportunities. Also, when researchers are overwhelmed by the number of options available, they tend to default to the most familiar method, which can result in a lack of innovation.

Collaborative Overload: Scientific research requires collaboration between multiple scientists, universities, and institutions. However, collaborative overload can result in redundancy, repeating experiments in a different agency, lowered efficiencies, and stalled science.

Technological Overload: With technological advancements, scientific research is becoming more data-driven than ever. However, the flood of data has resulted in a technological overload, leading to tools and software development, sometimes of questionable value.

Be a good scientist. Take notes. Make your work auditable and replicable at least a bit because the world is brutal, my fellow researcher. Scary place. Wonderful but scary.